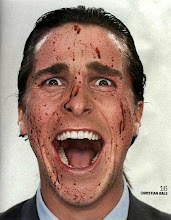

Ok so, full admission, this is like, not, actually like, a book I enjoy reading. Its not that I dont like it, its just that American Psycho is horribly boring. Thats half the point, I know, but still. Its one of those books that is much more fun to talk about than read (im looking at you Joyce!). Not only that, Ellis is such an asshole to everyone and everything in the book, I mean, its kind of petty, but its so refreshing. Im so fucking tierd of people acting like offending people is the worst thing ever. In the words of Ellis "So fucking what?"

Its an odd thing to contrast this book with Lolita. Nabokov takes a horrible protagonist and works hard the entire book to make you love him. He is humanized by the end of the novel, he isnt just a pervert or whatever. In part I think this is some kind of, perhaps not so subtle, humanism that Nabokov is pulling. Contrast this with Ellis in AP. He begins with a morally reprehensible human being and never tries to redeem him. He makes you hate him even further than you might otherwise expect. Not only is Bateman a horrible murderer and total fucking asshole, he is boring as fuck. I cant remember who it was, they called Ellis's writing the "aesthetics of boredom" or something to that effect. Totally hits it on the head. There is this old quote by John Ruskin about how "there are two kinds of artist, those who create what they are in their art, and those who create what they want to be." I tend to think of this as a truism about art but when applied to both instances of Nabokov and Ellis in these two books im not sure how it squares. They obviously both think they are horrible beasts or villains. But Nabokov works to humanize himself whereas Ellis just plunges further into his own nihilistic, dehumanizing fantasy. It is, I think, one of the most incredibly self critical books I have ever read.

Now, this is all assuming that you actually think that the author is writing himself into the book at this point. This is actually a fascinating question. I dont have a particularly firm stance on it. On the one hand it seems like some kind of logical fallacy that an artist, from within their own mind, might be able to create something that is not a reflection of them or their environment. Simultaneous to this, it is also obvious that on a literal level an artist is not exclusively writing themselves into the work. Also this assumes that the artist is actually saying what they want to say. In my experience, people, artists included, rarely say what they mean or mean what they say. I have, for instance on this blog, unintentionally said things many times that I only catch reading over later. There are themes and threads, you might call them meta-narratives (IF I SEE THAT GODDAMN WORD ONE MORE TIME!) of sorts within the blog. Wherein you might come to an understanding of things I wrote by looking at all of the things on the blog rather than at individual posts. I dont think any writer is any different.

But I think it is unavoidable to see both of these characters, Bateman and Humbert, as extensions of the author. Particularly with Ellis, being that he has variously said that Bateman was based on himself, or a part of himself at the time, or off of his father. Which is getting more and more interesting as an interpretation the more I think about it . . . anyway. Particularly if you read the novel as being about Ellis and Batemans murders being an analogy for Ellis being gay. In fact, the entire story actually makes sense at that point. Bateman isnt even enigmatic at all thought of in this way. Although I just said I dont think artists always mean what they say or say what they mean, ive got to say, I think Ellis is intentionally writing himself into the story in a very clear and visceral way. This is why I say its so self critical. Particularly when compared with Nabokovs Lolita which revolves constantly around self condemnations and self justifications. Ellis denies Batemans own humanity, pushes civilization and whatever you might think of as human, further and further away. Into some kind of abyss of hatred and jealousy. This of course just makes me love Ellis that much more. Because im that same kind of asshole on the inside.I dont want to be part of any club that would have me as a member. Also I fucking hate it when people sympathize with me. I dont have a fucking vagina, I dont want to talk about my feelings. I used to have this economics professor who said that the reason everyone on wall street was so greedy and always acted in their own self interest was because they had "the evil gene" and welp, it just meant they were born evil. It was a joke of course but its as good an explanation for why Ellis is Ellis and Bateman is Bateman . . . Evil Gene . . . when in doubt make shit up. I wonder if that was my professors version of the selfish gene? I think Ellis actually gives something approximating an explanation for his own internal life with the Notes from the underground quote in the beginning of the novel . . . anyway, ill complete this post later, I have to guy buy whiskey and powdered graphite because . . . ART!

Its an odd thing to contrast this book with Lolita. Nabokov takes a horrible protagonist and works hard the entire book to make you love him. He is humanized by the end of the novel, he isnt just a pervert or whatever. In part I think this is some kind of, perhaps not so subtle, humanism that Nabokov is pulling. Contrast this with Ellis in AP. He begins with a morally reprehensible human being and never tries to redeem him. He makes you hate him even further than you might otherwise expect. Not only is Bateman a horrible murderer and total fucking asshole, he is boring as fuck. I cant remember who it was, they called Ellis's writing the "aesthetics of boredom" or something to that effect. Totally hits it on the head. There is this old quote by John Ruskin about how "there are two kinds of artist, those who create what they are in their art, and those who create what they want to be." I tend to think of this as a truism about art but when applied to both instances of Nabokov and Ellis in these two books im not sure how it squares. They obviously both think they are horrible beasts or villains. But Nabokov works to humanize himself whereas Ellis just plunges further into his own nihilistic, dehumanizing fantasy. It is, I think, one of the most incredibly self critical books I have ever read.

Now, this is all assuming that you actually think that the author is writing himself into the book at this point. This is actually a fascinating question. I dont have a particularly firm stance on it. On the one hand it seems like some kind of logical fallacy that an artist, from within their own mind, might be able to create something that is not a reflection of them or their environment. Simultaneous to this, it is also obvious that on a literal level an artist is not exclusively writing themselves into the work. Also this assumes that the artist is actually saying what they want to say. In my experience, people, artists included, rarely say what they mean or mean what they say. I have, for instance on this blog, unintentionally said things many times that I only catch reading over later. There are themes and threads, you might call them meta-narratives (IF I SEE THAT GODDAMN WORD ONE MORE TIME!) of sorts within the blog. Wherein you might come to an understanding of things I wrote by looking at all of the things on the blog rather than at individual posts. I dont think any writer is any different.

But I think it is unavoidable to see both of these characters, Bateman and Humbert, as extensions of the author. Particularly with Ellis, being that he has variously said that Bateman was based on himself, or a part of himself at the time, or off of his father. Which is getting more and more interesting as an interpretation the more I think about it . . . anyway. Particularly if you read the novel as being about Ellis and Batemans murders being an analogy for Ellis being gay. In fact, the entire story actually makes sense at that point. Bateman isnt even enigmatic at all thought of in this way. Although I just said I dont think artists always mean what they say or say what they mean, ive got to say, I think Ellis is intentionally writing himself into the story in a very clear and visceral way. This is why I say its so self critical. Particularly when compared with Nabokovs Lolita which revolves constantly around self condemnations and self justifications. Ellis denies Batemans own humanity, pushes civilization and whatever you might think of as human, further and further away. Into some kind of abyss of hatred and jealousy. This of course just makes me love Ellis that much more. Because im that same kind of asshole on the inside.I dont want to be part of any club that would have me as a member. Also I fucking hate it when people sympathize with me. I dont have a fucking vagina, I dont want to talk about my feelings. I used to have this economics professor who said that the reason everyone on wall street was so greedy and always acted in their own self interest was because they had "the evil gene" and welp, it just meant they were born evil. It was a joke of course but its as good an explanation for why Ellis is Ellis and Bateman is Bateman . . . Evil Gene . . . when in doubt make shit up. I wonder if that was my professors version of the selfish gene? I think Ellis actually gives something approximating an explanation for his own internal life with the Notes from the underground quote in the beginning of the novel . . . anyway, ill complete this post later, I have to guy buy whiskey and powdered graphite because . . . ART!

THE CENTER CANNOT HOLD:

Towards a Better

Understanding of American Psycho's

Patrick Bateman

Probably one of the most violent,

offensive, and ironically, boring novels in the latter half of the

last century, Bret Easton Ellis's American Psycho stands as a

contemptuous rebuke to anyone that might happen to read it. "ABANDON

ALL HOPE

YE WHO ENTER HERE" rings out as the first line of the novel

(Ellis 2). A

hallucinatory cacophony of advertising copy, pornography, apocalyptic

prose, slasher flicks, fashion magazines and the Zagat guide all

rolled into one, American Psycho is

such a peculiar blend of our modern American fabric that it is at

times unintelligible. Patrick Bateman, a self described "fucking

evil psychopath," narrates this misanthropic tale, and the

various interpretations of the novel largely revolve around the

interpretations of his character (Ellis 15). Although Wayne Parry,

writing in the International Review of Psychiatry, believes that

Bateman "fails to meet the criteria for a psychopath," he

certainly doesn't qualify as normal (282).

Martin Rogers,

in his "Video Nasties and the Monstrous

Bodies of American Psycho,"

notes a common response of readers to the novel: "Patrick's

narrative threatens and repulses," it is a "refutation of

the act of reading, rendering it a half-creature of the literary

margins" (234). Most criticism has revolved around the notion

that Bateman is created as some kind of dense, labyrinthine critique

of the world in which he exists. As if the novel was created as a

puzzle or riddle to be unlocked by only the most clever readers

(these are invariably the readers who are writing the critiques).

This complexity skews towards a kind of obscurantism that

unnecessarily complicates the novel, and simultaneously ignores its

most outrageous passages. Though no assessment

of a work of art can be said to have any objective

validity, the novel Ellis

presents is not a critique of any social, cultural, or political

system. Instead, it is a search for catharsis, in which Bateman

attempt to find value in his life by destabilizing his own inexorable

nihilism.

Unreality permeates the novel,

particularly as it pertains to the most infamous element in the

story, murder. The violence of the book is portrayed in an intense,

pornographic, style. In fact, numerous scenes dovetail seamlessly

from "hard-core

montage" into murder (Ellis 222). The descriptions

of the murders and their aftermath are so blatantly unhidden, and

uncensored, both from other characters in the novel and the reader,

that many have assumed they do not actually occur. Rogers remarks on

the impact of the violence: "When the gore arrives midway

through the book, it is indeed like an anxiety attack for the reader"

(233). Bateman chainsaws a women in half at one point and this

presumably arouses no suspicions from anyone in the building (Ellis

243). This disbelief in the events as portrayed is largely the view

that Mary Harron takes in her film adaptation of the novel, American

Psycho. Produced well after the end of the 1980s', it is a

natural take for Harron's film to be conceived largely as a satire.

Mary G. Hurd, who writes a biographical sketch of Harron in her book

"Women Directors and Their Films," recounts the

difficulties Harron had in making the film: She was nearly thrown off

the project and replaced by Oliver Stone, and was forced to edit some

of the sex scenes or face an NC-17 rating (65). The violence is

re-imagined in the film. Marco Abel in his article "Judgment is

Not an Exit: Toward an Affective Criticism of Violence with American

Psycho," notes that the films violence "functions

merely as a metaphor for capitalism's cannibalistic cruelty - one

that can be accepted precisely because it merely allegorizes the

larger point of the novel" (142). Although there are satirical

elements in the novel, they are complex undertones compared to the

rather conventional presentation of the film. The music in particular

is used to underline the ridiculousness of the era and the murders,

as in the scene in which Paul Allen is killed while "Hip to be

Square" By Huey Lewis and the News irreverently plays in the

background (Harron). The songs goofy lyrics, contrasted with Allen's

murder, encapsulate the themes of the film so well you might be

excused for thinking it was composed specifically for it. Though

provocative in its own right, Harron's film sanitizes Ellis's novel,

perhaps in part to avoid the kind of backlash from critics the book

had upon its release. Abel comments on this compromise: "critical

discourse affirms her satirical strategies and praises her decisions

to alter the novel so that just about everything offensive about it

has disappeared" (142).

Though disbelief in the events of the

story makes it perhaps more plausible (and palatable), it fails to

grapple with much of the substance of the novel. Abel articulates

a conventional criticism of an unreal story

like that found in the novel: "The closer art resembles

life, the higher its value; the less accurate its representation -

the more dissimilar the copy is from the original - the more

questionable its merit" (138). Ellis's writing is too enigmatic,

perhaps too sophisticated, for the didactic moral readings found in

the film. This is not an emperor has no clothes type

satire. There is in the novel, just beneath the surface, an intense

affection for Bateman's world of vapid materialism and the easy life

of idle rich men. Ellis's contempt for this world is one bred of

familiarity. If Bateman's life is empty, it is not a symptom of late

20th century capitalism. Instead, the blame is laid purely

at the feet of human existence itself: "It did not occur to me,

ever, that people were good or that a man was capable of change or

that the world could be a better place through one's taking pleasure

in a feeling or a look or a gesture, of receiving another person's

love or kindness. Nothing was affirmative, the term 'generosity of

spirit' applied to nothing, was a cliché" (Ellis 274).

Viewing the novel as a critique of

consumerism, Reaganomics, masculinity, or a satire, misses the

nihilistic point of the novel (if we can for a moment consent to such

a contradictory term). Indeed, Bateman and the other characters have

a kind of aspirational conformity that is almost entirely

unchallenged throughout the book. "Why don't you just quit? You

don't have to work." Bateman's fiance asks him at one point.

"Because I want to fit in" Bateman responds (Ellis 174).

Ellis does not investigate the value of this attitude, instead he

"investigate the value of value itself" throughout the

novel (Abel 138).

The social justice crusade of a satire, or social critique, is parodied by Bateman himself. At dinner with friends he opines at length on the need for a social transformation of America: "But we can't ignore our social needs either . . .We have to provide food and shelter for the homeless and oppose racial discrimination and promote civil rights while also promoting equal rights for women . . . we have to promote general social concern and less materialism in young people" (Ellis 11-2). If Ellis critiques anything in his novel it is not materialism, or wealth, or inequity. Instead, it is the concerns of feminists, homosexuals, minorities, and anyone not vicious or wealthy enough to take everything they can from other people. Power, wealthy, and beauty are championed; they are the only redemption in an otherwise pointless, post-modern, godless America. Bateman does not search for our sympathy or understanding. As Volker Ferenz notes in his essay "Mementos of Contemporary American Cinema: Identifying and responding to the unreliable Narrator in the Movie Theater," "our allegiance with him is one of complete antipathy" (267). As Bateman declares at one point: "This is true: the world is better off with some people gone. Our lives are not all interconnected. That theory is a crock. Some people truly do not need to be here" (Ellis 164). Or in another one of his misanthropic reveries: "Reflection is useless, the world is senseless. Evil is its only permanence. God is not alive. Love cannot be trusted. Surface, surface, surface was all that anyone found meaning in… this was civilization as I saw it, colossal and jagged…" (Ellis 274)

Though Bateman's character is difficult

for some to countenance, the very structure of the novel seems to be

made intentionally excruciating for readers. Rogers remarks that the

novel has an "almost total resistance to plot or character

development, forcing the book to exist as a collection of forms and

formal discourses" (239). There is little if anything that

passes for plot arc either. You might open the book at any page and

begin reading and be just as well abreast of the story as if you had

began at the beginning. You would also be just as uninformed if you

had started at the end and read backward to the beginning. Nothing of

value is lost in this episodic reading, and it mirrors the very

structure of Bateman's personality: "It is hard for me to make sense on any

given level. Myself is fabricated, an aberration. I am a

noncontingent human being. My personality is sketchy and unformed"

(Ellis 276). Ellis creates a mind numbing "private maze"

for the reader, as well as Bateman (254).

Speaking of

the excesses of both the murders and the prose Rogers notes, "these

passages are, structurally speaking, no different in combinatorial

'value' than the long passage in the early chapter 'Morning' wherein

Patrick describes his morning grooming ritual" (233). The

excruciating minutiae of the novel is at times almost as difficult to

read as the murders. Far from being satire, social criticism, or

erotica, violence is portrayed as an attempt at circumventing

Bateman's own nihilism. "It is precisely the novels excess of

violence that overwhelms, frustrates, annoys, upsets, and even

sickens; it is this (literal) overkill that provokes readers to throw

away the book, to tear it apart, to spit at it and, potentially, to

talk or write about it" (Abel 144). One wonders if the chorus of

voices attempting to understand the inane and repetitive nature of

the narrative is not so dissimilar from the narrative itself.

Although it has been the subject of

intense scrutiny, I would argue that Batemans violence against women

actually says very little about Batemans attitudes towards women. The

violence against women in the book is a very specific twist on the

atrocious nature of Bateman. It is not enough to kill a man, as

societies ideal of men is virile and independent. Women on the other

hand are seen, by feminist writers and others, as victims without

agency that need defending. Bateman's murders and rapes (the two are

almost always simultaneous in the novel) of women do not show Ellis's

hostility to women, instead, they work to underline the "impaired

capacity to feel" in the novels central character (Ellis 254).

As Vartan Messier explains in his essay "Violence, Pornography,

and Voyeurism as Transgression in Bret Easton Ellis's American

Psycho," "The irony of Ellis' minimalist prose style

. . . is that they relegate the responsibility for feelings and

emotions to the reader . . . the reader is able to feel what Bateman

does not—namely, feelings of disgust and repulsion for the acts of

sexual violence" (86). The violence against women reinforces

Bateman's orgiastic "bloodlust" and demonstrate his

inhumanity to those humanity deems most in need of societies defense,

namely women (Ellis 206). Complicating this, the murders mix both

predation and retaliation. Many of the women and men that Bateman

kills have had some kind of power or rank over him. As with his

ex-girlfriend Bethany, in the novel, or Paul Allen in the film.

Many have voiced outraged at the

violence in the novel, such as Jane Caputi in her article "American

Psychos: The Serial Killer in Contemporary Fiction." To

summarize, she sees Bateman's murders as a mirror to the reality of

violence perpetrated against women in contemporary America, and

implies that this type of fiction can encourage that same violence

(104). The outrage seems to be directed at the perceived misogyny of

Ellis, rather than the fact that people are being tortured and

murdered en mass in the novel. This should not be seen as a fault of

Caputi's assessment however. Richard Giles notes in his essay “I

Hope You Didn’t Go into Raw Space without Me”: Bret Easton

Ellis’s American Psycho,"

"At times one feels that Ellis is deliberately writing the most

politically incorrect novel imaginable" (161).

Though the violence against

women is overt, it is not in isolation. Mark Storey, in his article

"And as Things Fell Apart," characterizes this violence as

"a wish to objectify women in purely aesthetic terms and to deny

them any interiority or autonomy that might threaten masculine

superiority" (66). Storey gets it half right. No one is safe

from the dehumanizing aestheticization of being a murder victim in

the novel. Throughout the story Bateman murders: bums, dogs, taxi

drivers, puppies, prostitutes, coworkers, a five year old boy, street

performers, police officers, rats, his fiance, his fiance's

neighbors, delivery boys, maids, socialites, call girls, and

competing businessmen, to name a few. The list of people he does not

kill is almost more telling than the list of people he does. He

is on the verge of killing both Jean, his secretary, and Luis

Curuthers, a closeted homosexual coworker, both of which are in love

with him, numerous times, but does not. Caputi and other critics

argue that such serial killer narratives "terrorizes women . . .

and empower men," but Bateman specifically contradicts this

reading in the novel (101): "I want my pain to be inflicted on

others. I want no one to escape. But even after admitting this - and

I have, countless times, in just about every act I've committed - and

coming face-to-face with these truths, there is no catharsis. I gain

no deeper knowledge about myself, no new understanding can be

extracted from my telling" (Ellis 276). These murders are not

performative, they are not a symbolic attack, or defense, of

anything. The victims of the murders are not the object of concern

for Bateman, instead it is his own intense, apocalyptic, and

meaningless internal world.

A satirical or moralistic reading of

the novel condemns the reader to the same kind tautology that Bateman

is trapped in. It is an endless reexamination of entrails. The facts

of the murders, whether they did or did not happen, are largely

irrelevant, as is any moral validation or condemnation of the events

of the novel.The violence and ennui work together to create the

impressionistic effect of the novel. As Abel observes: Ellis's

abandonment of any pretense to characterization, psychology, or

motivation paradoxically lures readers into longing for the very

violence Ellis does to English prose. Readers prefer the affective

quality of prosaic boredom to that of heightened graphic

aggression, yet it is of course the exposure to the former that

affects and effectuates the response to the latter . . . the text

decidedly exists on both levels, as evidenced by the forcefulness

of the critical responses to it: that of the actual physical

violence committed by Bateman and that of the prose itself (143).

If the structure or subject

matter of the novel provoke or frustrate readers it is no accident.

Moreover, it is a common theme of post-modern fiction to insist that

the reader find their own meaning in the text, even if they arrive at

the conclusion that the text itself is meaningless. Taking the long

view of American fiction through an examination of two very different

books, Sylvia Soderlind in her essay, "Branding the Body:

American Violence and Self-fashioning from The Scarlet Letter

to American Psycho," concludes: "If THIS—being a

postmodern American in a world in which interiority doesn’t matter,

where value has no meaning outside the world of commerce and where

nation signifies exclusion—does not offer an exit from hell, then

our task as readers is to look for its potential counterpart—THAT

which might" (76).

Though catharsis evades

Bateman throughout the book, it is still possible to parasitically

indulge in it for the reader. Whether by examining the novel,

engaging with its more difficult passages, or quiting it altogether .

An impressionistic bend would be well advised, as Bateman's warts are

many. Living beneath them is a sphinx, and though its nature is

mysterious, its vitality and intensity is unquestioned.